Shell Patterns and Populations of Japanese Island Snails

Studies into the evolution of variable traits is crucial to cementing our understanding of evolution. The applications of which are instrumental in protecting the natural world. My research looks into a potential relationship between the patterns seen in Japanese island snail shells and how the snails are distributed across their habitat. This project looks to highlight how evolution, in relation to an individual’s appearance, can shape populations.

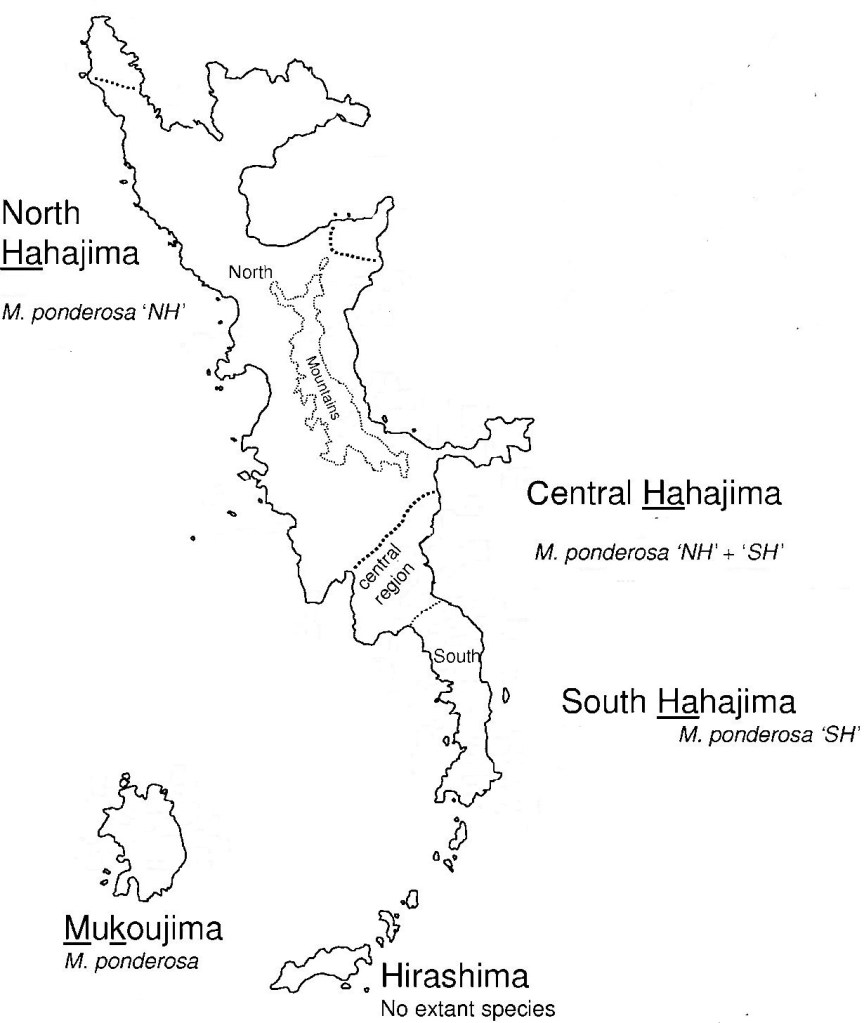

To give some context to the project the study species was selected due to unique scenario presented by the islands they are found on. The Ogasawara Archipelago, also called the Bonin Islands, are located approximately 1000km south of Tokyo. The name “Bonin” comes from the Japanese “bunin” to mean uninhabited or “no people”. Whilst this name may no longer be entirely accurate, many of the islands are now inhabited, the primary island looked at by this study has been relatively unaffected by humans. Mukoujima island is currently not occupied by humans, this has been the case for most of its history prior to WW2. During the war the islands were used as part of a Japanese military base. This relative isolation makes the islands an interesting place to study evolutionary and ecological processes with reduced human influence.

The island snails are interesting for a number of reasons. Interest in the Genus (Mandarina) as a whole comes from the adaptive radiation (where one ancestral species rapidly diversifies into multiple species to occupy new niches) seen in their evolutionary history. In the case of Mandarina, a Japanese mainland species found its way to Ogasawara and went from one to 14 species.

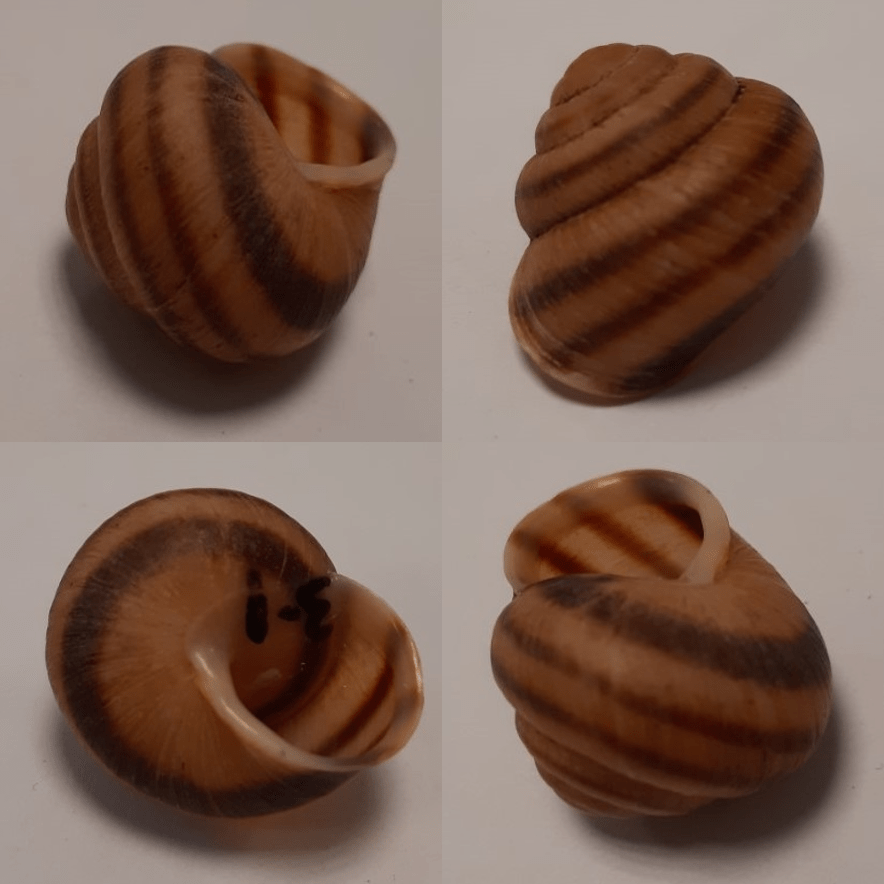

The species Mandarina ponderosa (From now M. ponderosa) is the primary focus of the study and the sole Mandarina inhabitant of our island of choice, Mukoujima. Shells of the species, as well as genetic data, were collected by my supervisor Angus Davison and collaborator Satoshi Chiba (meaning my project did not involve a trip to Japan). The shells of these species usually have three dark bands running over a lighter base colour that follow the spiral of the shell. Variation can be seen in the thickness of these bands, sometimes being so thick bands merge, or in other cases a band may not show at all. This variation may have an impact on the predation of these snails as well as how they interact with each other.

Initially the project was going to look at the colour of shells using a spectrophotometer. This is a machine that gives a reading of an objects colour by shining a pure white light at it and measuring what wavelengths of light are reflected. This research would have followed the trend in measuring reflectance to categorise colour in an unbiased way (preferable over judging by eye) which has been carried out previously with other snails. Unfortunately, this project did not come to fruition due to the spectrophotometer needing a part replaced that could not be fixed in time. For me to use.

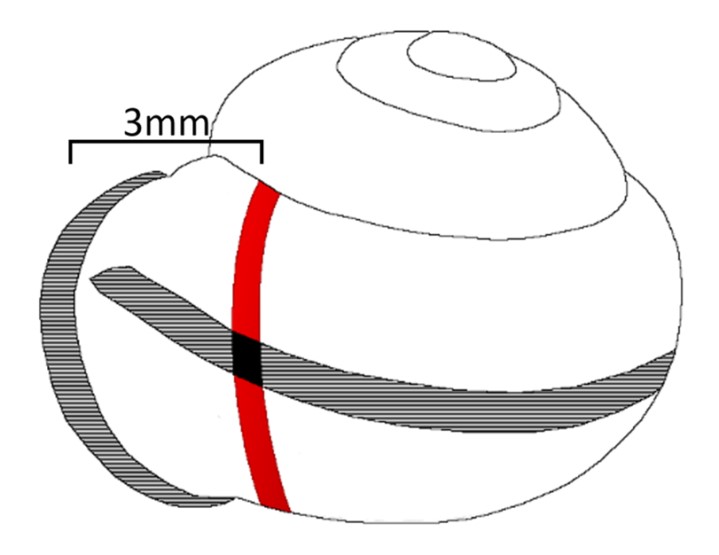

Unable to measure colour, I used banding pattern as an assessment of variation in shell patterns. Pattern and contrast may be key in the perception. As the shells vary in shades of brown, banding maybe more definitive in categorising the shell variation. To measure the bands, I used a simple but effective method to collect data devised by Hannah Jackson, a PhD student carrying out similar research. Snail shells have growth ridges that wrap perpendicular the spiral of the shell, forming as part of how the shell is developed. We placed a thin piece of electrical tape around one of these ridges 3mm away from the lip of the shell and marked the start and end of each band across the tape as well as the end of the growth ridge.

Currently all the data has been collected (just shy of 500 snails) and I am about to carry out all the data analysis. The first step in this will be using two pieces of software, STRUCTURE and genepop, to analyse the bank of genetic data giving insight into the population structure of M. ponderosa on Mukoujima. I will also be looking to see if there are any ways to group different banding patterns. Once the these are defined, I will look to see if there is a significant relationship between the two. I will also implement other data that has previously been collected such as habitat and size.

The final step in my project is to take the coordinates of the sample sites on the island and produce a number of maps that display how the different traits of M. ponderosa are distributed across Mukoujima. These maps may help reveal new patterns and create directions for further research.

Now the spectrophotometer has been fixed, the next step would be to collect the colour data we originally set out for and see how that relates to the genetic data, as well as the data that I have collected on banding pattern. Following this, similar methodologies can be applied to other Mandarina to get a greater picture of the evolutionary dynamics of snails in the Ogasawara archipelago.

Useful Links:

Angus Davison and Satoshi Chiba on the Mandarina genus: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.02990.x

Angus Davison, Hannah Jackson, Ellis Murphy and Tom Reader on measuring shell colour: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41437-019-0189-z

Angus Davison Lab: https://www.angusdavison.org/index.php/research