The evolution of polymorphism in the warning coloration of the Amazonian poison frog Adelphobates galactonotus

In November 2019, Heredity published the work of Diana Rojas and colleagues which explored the evolutionary origins of warning colourations in the Amazonian poison frog (Adelphobates galactonotus in Latin). I found this paper when reading around the subject for my own project (which you can read more about here). The different colour types provide an insightful tool into assessing relative contributions of natural selection, genetic drift and geographic distributions to how this trait evolved. Colour as a trait has long since been a key factor in clarifying our understanding genetics and evolution, going back to fundamental principles of genetics.

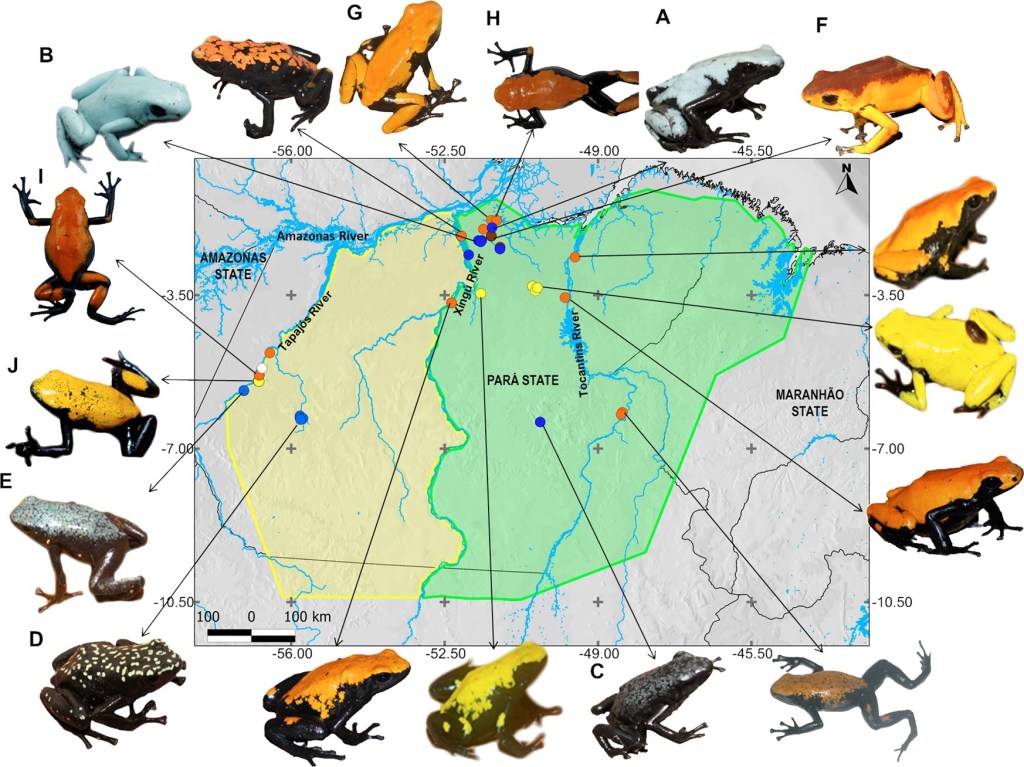

The study species of poison frog, A. galactonotus, are usually grouped into colour categories of yellow, orange, blue, red, and brown. The colour of the frogs is a warning signal to predators, advertising their toxicity. Interestingly multiple frog colours are not observed in a single area. A single population will consist of only one of the colour categories. Found in east Amazonia, this species does not show clear boarders in colour (i.e. blue in west, yellow in east, etc…) instead forming a mosaic pattern. Below is a figure from the paper which shows the sampling areas split east and west by the Xingu river and demonstrates the mosaic pattern of colour distributions.

The paper looked to combine genetics and geographic factors with colour data to test three hypotheses:

- The colour diversification of A. galactonotus occurred at the same time as colour diversification in other neotropical frogs.

- The same colouration may have evolved multiple times in different locations, independently of each other.

- There is a selection pressure acting on frog colour driving the evolution of the trait.

The study used a spectrophotometer to re-assess their measures of colour, much like I intended to do with my own research project. The benefit of this compared to judging by eye is that you are able to take the data given on what wavelengths the frogs reflect and apply this to models of vision for predators (birds) or the frogs. This is a more effective approach as it is more representative of the natural systems colour traits have evolved in.

What they found was that A. galactonotus colour can be cut down to four categories. No longer classifying any as red. The data grouped the frogs into yellow, orange, blue or brown. There were no frogs that fell in between these colour groups. They did note that within the blue category there was substantially more variation in both colour as well as in the pattern of their colours. Consistently with previous studies, frogs from a single population all fell within the same colour category. It was also found that both frogs and birds would be able to distinguish between the four colours, with birds more able to recognise more subtle variations in colour.

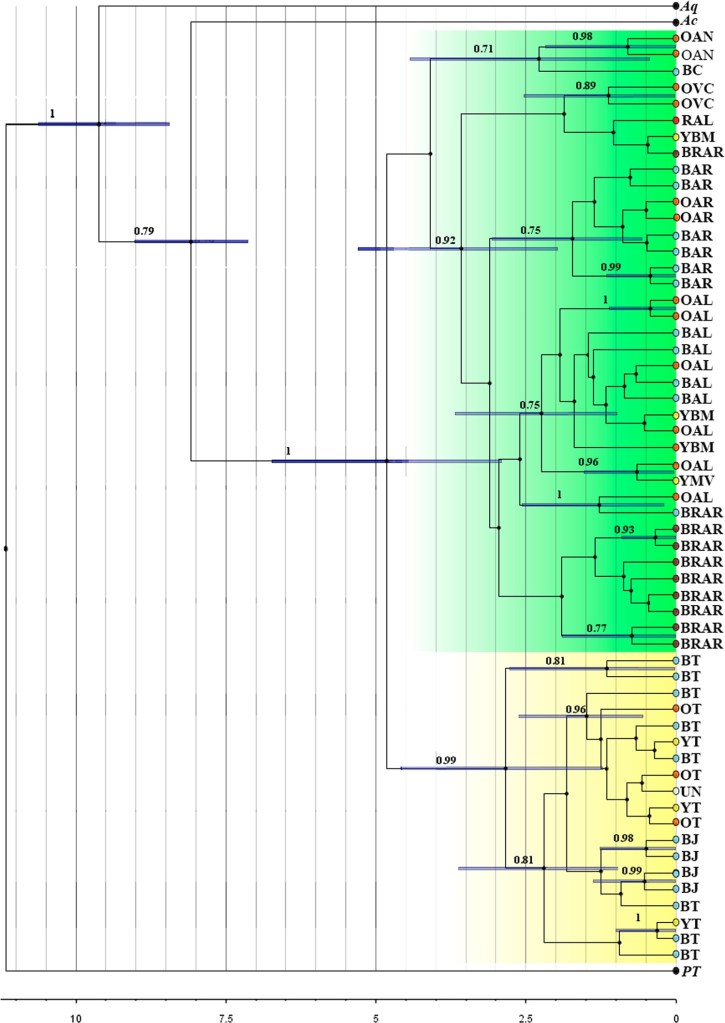

Looking at genetics, they looked to track the divergence of A. galactonotus and see if it matched with how colour was distributed, but they found no strong link between the two. They also used the genetic data to produce a tree which mapped the divergence, showing were different populations separated out from each other (shown below). A key observation from this being that there are two distinct groups formed equating to either side of the Xingu river. This suggests the river acts as a barrier to genes spreading among the species.

To summarise their findings, they did not identify a relationship between the population genetics and distributions of colour, and instead that geographic distributions and occasions of isolation were more closely related to the genetic structure. They were unable to find that colour was under selection, suggesting much of the colour variation is the result of relatively recent colour mutations becoming fixed (found in all individuals) within the populations they arise in. The model of the evolutionary history suggests that any large-scale genetic divergence that would be associated to colour would have occurred within the Pleistocene (2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago).

The paper offers some further direction leading on from the work that they have done, centring around the idea of the mosaic colour distributions, and asking the question: What is stopping these different colour populations from breeding with each other if they are so close together? From their results showing that the frogs would be able distinguish between colour categories, they suggest that assortative mating by colour has become beneficial, suggesting that colour hybrid offspring may be less likely to survive. They also suggest that further work into identifying if polymorphisms (variable traits) are precursors to speciation (the process of one species separating into two) which is a key theme of my own project.

Useful Links:

The paper – limited access: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41437-019-0281-4

IUCN Red List – Conservation information: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/55185/11253730

First Image Link: https://calphotos.berkeley.edu/cgi/img_query?seq_num=153830&one=T